By François Soudan

On 17 January 1961, just sixty years ago, the first legally elected prime minister of the DRC was assassinated after being overthrown with help from Washington. A sinister episode that Larry Devlin, the ‘Mr. Congo’ of the CIA from 1960 to 1967, would reveal half a century later in his fascinating book, ‘Chief of Station, Congo: Fighting the Cold War in a Hot Zone.’

Leopoldville, on 30 June 1960. With the declaration of its independence, the DRC finally emerges from its long colonial history. A new bilateral system is established with a head of state as cunning as he is impenetrable, Joseph Kasavubu, and a Prime Minister as charismatic as he is unpredictable, Patrice Lumumba. In bars, people dance to the rhythm of the Independence Cha Cha, but the euphoria will be short-lived.

On 5 July, a mutiny broke out in the Thysville camp (Mbanza-Ngungu), then spread to the capital. Over a matter of pay, no doubt, but also a revolt against the continued Belgian presence in the DRC by virtue of bilateral agreements. “For the army and General Janssens, who commands it, has the impudence to say that independence means nothing.”

On 11 July, the rich province of Katanga, where the Belgian “Mining Union” reigns, secedes under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe. South Kasai threatens to do the same. This new state-continent is on the verge of imploding.

A tough guy

It is in this context that the new CIA station chief landed at Leopoldville Beach on 10 July 1960. A CIA agent since 1949, Lawrence (Larry) Devlin is an experienced man and a tough guy. His “cover” is that of an ordinary consul, and his local boss is US Ambassador Clare Timberlake.

Very quickly, the two men believed in the same thing, shared in Washington by their superiors: Prime Minister Lumumba, the Kasai nationalist and co-founder of the powerful Congolese National Movement, is a dangerous man. A communist? No. A USSR agent? Probably not. A man who could be easily manipulated by the Soviets and the KGB? Certainly. It is therefore necessary to do everything possible to isolate him.

Bottom of Form

With the utmost discretion, Devlin then begins to sound out, with a view to possible recruitment, some of the most prominent Congolese political leaders, reputed for their animosity towards Lumumba. They include Albert Kalonji, leader of the Balubas of South Kasai, Paul Bolya, a Mongo leader from Ecuador, Pierre Soumialot, Lumumba’s own private secretary, the trade unionist Cyrille Adoula and, above all, the man who would become one of his most loyal contacts, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Justin Bomboko.

During the month of July 1960, the situation deteriorated a little more each day. In Matadi, on the Atlantic coast, Belgian parachutists were deployed to protect their compatriots from the Congolese army who were fighting with heavy weapons.

On the 13th, Lumumba announces the rupture of diplomatic relations with Belgium and threatens to call for Soviet intervention if the Westerners do not move. On the 17th, a first contingent of UN peacekeepers landed at N’Djili airport, led by British General Alexander, who said: “Congolese politicians have not yet come down from their trees.”

A maelstrom of violence and looting

At the heart of this maelstrom of violence and looting, the Americans are more obsessed than ever with the Prime Minister. Not only do the socialist chancelleries – the USSR, Czechoslovakia, China, East Germany, Ghana, Guinea – support Lumumba, but his own entourage is, according to the CIA, full of “KGB agents.”

We are in the middle of the Cold War, and the Americans will stop at nothing to counter their target. Learning that the prestigious Time magazine is planning to publish a cover story about Lumumba, Ambassador Timberlake warns his counterpart in Belgium, who calls up his friend Henry Luce, the magazine’s owner. The result: Lumumba disappears from the cover in the name of America’s supreme interests.

In a wired message to CIA headquarters, Devlin wrote: “Patrice Lumumba was born to be a revolutionary, but he doesn’t have the qualities to exercise power once he’s seized it. Sooner or later, Moscow will take the reins. He believes he can manipulate the Soviets, but they are the ones pulling the strings.”

Bottom of Form

On 26 August 1960, Allen Dulles, the director of the CIA, replied: “If Lumumba continues to be in power, the result will be at best chaos and at worst an eventual seizure of power by the communists, with disastrous consequences for the prestige of the UN and the interests of the free world. His dismissal must therefore be an urgent and priority objective for you.”

While Ambassador Timberlake is working to convince President Kasavubu to dismiss Lumumba (this requires a parliamentary vote), Devlin is working to undermine the Prime Minister’s authority. With the help of agitators hired for the occasion – he had a budget of $100,000, a considerable sum at the time – the CIA station chief organised anti-Lumumba demonstrations that often degenerated into violence.

On 5 September, Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba and replaced him with Joseph Ileo. However, the nationalist leader fights back, refuses to leave his post and wins parliamentary backing. The constitutional path seems blocked. The CIA believes the time has come to get down to business: the coup d’état.

The enigmatic Joseph-Désiré Mobutu

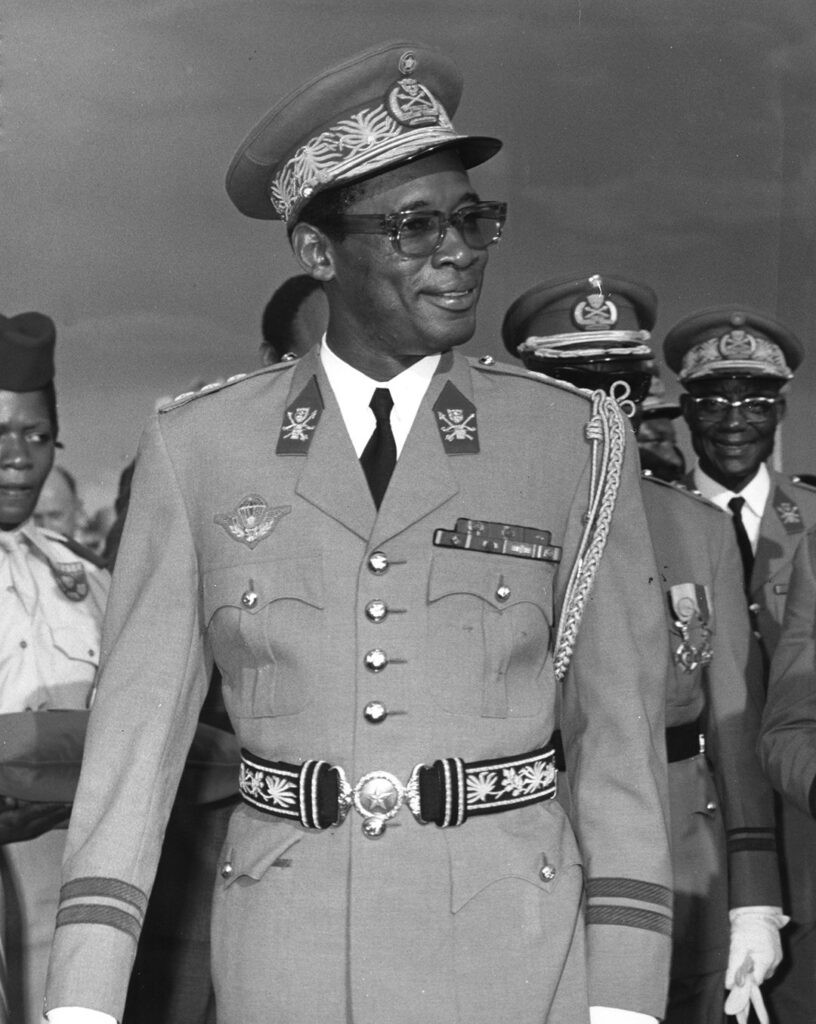

After Lumumba’s death, Mobutu rehabilitated Kasa-Vubu as head of the country but kept him in command of the army, which was facing a rebellion led by followers of the assassinated Prime Minister… until he took official power on 24 November 1965. © Archives Jeune Afrique

It was then that a certain Joseph-Désiré Mobutu appeared. Admittedly, the man is not a stranger to the Americans, but they misunderstand his motivation. On the one hand, they consider him temperate, competent and pro-Western; on the other, they are unaware that he was one of Lumumba’s closest collaborators, who made him Secretary of State and then Chief of Staff of the army. In short, this colonel, barely 30 years old, is still an enigma – one that will soon become clearer.

One evening in early September 1960, Devlin had a meeting with Kasavubu at the president’s house. While he is waiting in the living room, Mobutu appears. “I wanted to talk to you very much,” he said. “I’m tired of these political games, this is not how we are going to build a strong, independent and democratic Congo. The Soviets have invaded the country. Do you know that they sent a delegation to Camp Kokolo to teach Marxism to the soldiers and distribute their propaganda? They claim that you Westerners are plundering the Congo whereas they are our real friends. I spoke to Lumumba about this. He told me to mind my own business. I gathered together my zone commanders: they all agreed with me. So let me be clear. The army is ready to overthrow Lumumba and set up a transitional government made up of my supporters. Will the US help us?”

At this point in the conversation, Foreign Minister Bomboko, whom Devlin considers practically one of his agents, enters through a back door. Before sitting down next to Colonel Mobutu, he slips Devlin a little note folded in half on which he has written : “Help him.”

Convinced, the CIA station chief replied: “I can assure you that the US is willing to recognise a transitional government made up of civilians.” Mobutu has a final request: “I need $5,000 for my officers: if the coup fails, their families will be left penniless.” The request is granted.

On 14 September 1960, Mobutu seized power for the first time. Lumumba was arrested, a civilian government in which Bomboko remained foreign minister was appointed, and diplomatic relations with the USSR, China and Czechoslovakia ended. But there is a snag. Mobutu, who has placed Kasavubu under house arrest, is the de facto head of state. Devlin immediately went to see him: “You have a big problem of legitimacy,” he told him, “especially since you dismissed the National Assembly. Restore Kasavubu to power.”

“Legitimacy? You should say hypocrisy!” says an angry Mobutu. However, he will do it as he doesn’t have much of a choice. On at least three occasions in the weeks following the coup d’état, the CIA, filled in by one of its informants who is a part of the very Lumumbist Pierre Mulele’s entourage, allowed Mobutu to thwart assassination attempts.

Devlin personally gets involved by accidentally neutralising a killer while he was visiting his friend at the Kokolo camp. This creates a bond. The CIA’s Chief of Station no longer hides his admiration for this young colonel who not only possesses astonishing physical courage, but who is also capable of mastering a horde of rampaging and threatening mutineers by the mere magic of his words and charisma.

Mobutu is, after all, well surrounded. He is a member of the “Binza group”, who also advises him. This group is composed of people who are either “friends” of the CIA, or recruited by them: Bomboko of course, Adoula and the new director of Security, Victor Nendaka, a former right-hand man of Lumumba, originally from the Oriental Province and considered particularly brilliant.

An operation authorised by Eisenhower

That leaves, of course, the issue of Lumumba. Although placed under arrest, the former Prime Minister has still not left his official residence. Worse, in the eyes of the CIA, he is now protected by UN peacekeepers. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld’s representative in Leopoldville, Rajeshwar Dayal, whom the US considers highly suspicious, has learned that the Congolese soldiers will be replaced by those of the UN. Lumumba’s multiple statements are as courageous as they are inflammatory. In short, he must be stopped.

On 19 September 1960, Devlin received a secret message from Langley: “A certain ‘Joe from Paris’ will arrive in Leopoldville on 27 September; he will contact you, and you will need to work together.” On the designated day, he and “Joe” will meet in a bar and then in a safe house. “Joe” is a chemist who works for the CIA, and he has brought a whole collection of poisons to liquidate Lumumba.

“Who authorised this operation?” asks Devlin. “President Eisenhower himself,” replied “Joe,” adding: “It will be up to you and you alone to carry it out.” He then handed him a package containing the poisons: various powders and liquids for food, drink and even a special toothpaste. “If our man brushes his teeth with it, he will catch a staggering polio. He will be here today, gone tomorrow.”

Devlin, who is not convinced of the need to suppress Lumumba – “he’s no Hitler,” he thinks – nevertheless contacts his only agent within Lumumba’s entourage. But the agent withdrew: he did not, he assured him, have access to the kitchens and private flats of an increasingly distrustful Lumumba. Over the next few weeks, Devlin continued to drag his feet as Langley became more and more impatient: “Where are you at, Larry?” Larry would be saved by the bell.

On 27 November 1960, on a stormy night, Lumumba secretly left the capital to travel to Stanleyville (now Kisangani), his stronghold. He was arrested a few days later in Kasai, severely beaten and flown back to Leopoldville, before being incarcerated in the Thysville military camp.

Dayal begged Hammarskjöld to allow the Ghanaian UN contingent to attempt a rescue mission. But the secretary-general, under direct pressure from the Americans, does not grant this request. At the very least, the poisoning operation is abandoned.

“Let the Congolese take care of the Congolese”

As Antoine Gizenga, Mulele, Anicet Kashamura and most of Lumumba’s companions from Province Orientale to North Katanga, via South Kivu, launch the uprising, another American plan emerges: let the Congolese take care of the Congolese. In other words: let the army do the dirty work itself.

On 13 January 1961, the Thysville camp, where Lumumba was being held, erupted into mutiny. Very soon, the CIA learns that disgruntled soldiers have freed the former prime minister and are considering placing themselves under his orders. In Leopoldville, the whole government is in panic, except Mobutu and Nendaka, who, after seizing Kasavubu and Bomboko, fly to Thysville.

Once more, the chief of staff confronts his troops, brings them under his control and orders that Lumumba be arrested again. This hero of Congolese independence is thrown into a plane heading for Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi), the capital of the secessionist province of Katanga, where his sworn enemy Tshombe is waiting for him.

Lumumba, with his swollen face, was seen arriving on the airport tarmac on 17 January. He would be shot later that very same day. On 20 January, in Washington, President John Kennedy took office. In Langley, everyone welcomes the fact that the new administration will not have to deal with the Lumumba case.

theafricareport.com

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation