By Gerald Mbanda

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi arrived in Dar es Salaam on January 9, 2025 for a two-day visit to Tanzania. Image via Tanzania’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Sino–African partnership is often misunderstood through the narrow lens of dependency. Critics portray Africa as a passive recipient and China as a dominant donor. This framing ignores both history and reality. In practice, China–Africa relations are built on shared growth, shared experience, and mutual benefit. They are not a one-sided aid relationship, but a partnership shaped by common development goals and practical cooperation.

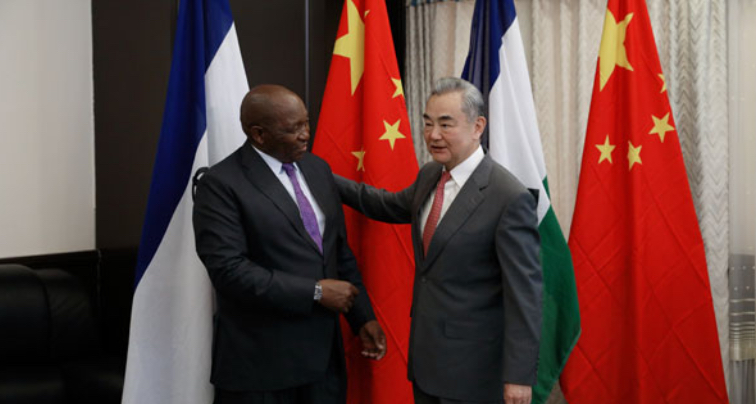

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has just concluded an African tour that took him to Ethiopia, Somalia, Tanzania and Lesotho from Jan. 7 to 12, continuing the unbroken 36-year tradition of Chinese foreign ministers selecting Africa as their first overseas destination each year. This is not symbolic charity diplomacy; it signals that Africa is a strategic partner, not an afterthought. The consistency of these visits underscores long-term engagement rather than short-term influence.

During his speech at the launch ceremony of the 2026 China-Africa Year of People-to-People Exchanges, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that, “In the face of a turbulent world, China and Africa more than ever need to uphold fairness and justice, strengthen solidarity and mutual support, and deepen exchanges and cooperation.”

Today, China and Africa have reached many areas of cooperation such as infrastructure, trade, industry, and human development which illustrate the shared-growth model. Infrastructure cooperation is one of the most visible areas. In Kenya, the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway reduced travel time and logistics costs, directly supporting trade and tourism. While Chinese companies built the railway, local workers were trained, employed, and later absorbed into operations and maintenance. The result is not simply a Chinese-built asset, but an African-owned transport corridor that supports regional integration.

In Ethiopia, Chinese-supported industrial parks such as the Eastern Industrial Zone helped kick-start manufacturing capacity. These parks attracted both Chinese and non-Chinese firms, created tens of thousands of local jobs, and enabled technology transfer in textiles, footwear, and light manufacturing. Ethiopia gained industrial know-how and export capacity, while Chinese firms benefited from new markets and efficient production bases. This is shared growth in practice, not extraction.

Energy cooperation offers another clear example. In Nigeria and Zambia, Chinese firms have worked on power generation and transmission projects that address one of Africa’s biggest development bottlenecks: electricity shortages. Reliable power enables African small businesses, factories, hospitals, and schools to function effectively. At the same time, Chinese companies gain experience operating in diverse environments and contribute to global energy solutions. The benefits flow in both directions.

Trade figures further challenge the dependency narrative. Africa exports not only raw materials to China, but increasingly agricultural products, manufactured goods, and services. Rwandan coffee, Kenyan tea, and South African wine now reach Chinese consumers through preferential trade arrangements and e-commerce platforms. African exporters gain access to a vast market, while Chinese consumers benefit from diverse, high-quality products.

Human capacity building is another pillar often overlooked. Thousands of African students study in China each year on scholarships, acquiring skills in engineering, medicine, information technology, and public administration. Many return home to work in government, private industry, or entrepreneurship. China, drawing from its own development experience, shares lessons on poverty reduction, rural development, and infrastructure-led growth—areas where African countries have explicitly requested cooperation.

Importantly, African governments are not passive actors in this relationship. They negotiate terms, set national priorities, and increasingly insist on local content, job creation, and technology transfer. Countries like Ghana and Senegal have renegotiated or redesigned projects to align with domestic development strategies. This agency undermines the claim that Africa is trapped in a donor–recipient dynamic.

The Sino–African partnership is not perfect, and challenges such as debt sustainability, environmental standards, and governance must be addressed transparently. However, framing the relationship as domination misses its core reality. It is a pragmatic partnership shaped by mutual interests, historical solidarity, and a shared belief that development is best achieved through cooperation.

Ultimately, China–Africa engagement is best understood not as dependency, but as a win-win process—one that delivers tangible benefits to ordinary people on both sides and evolves as both partners grow.

The author is a researcher and publisher on Africa and China development and Cooperation