By John Allen

Desmond & Leah Tutu Foundation

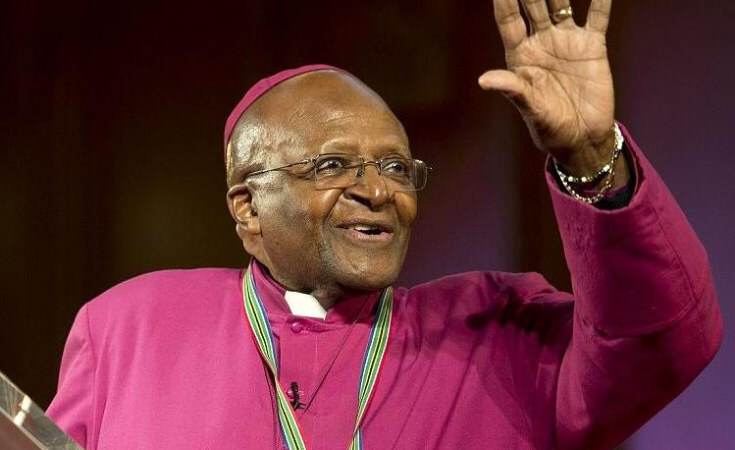

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu lived his life with passion, courage, faith and deep insight, but it was a life lived against the odds.

Sickly at birth, as an infant he survived polio, which left him with a permanently weakened right hand. As a teenager he suffered tuberculosis, which left adhesions on his lungs. Later in the 1980s, when he became, in Nelson Mandela’s words “public enemy number one” to the apartheid regime, he survived a number of assassination attempts. And for the last 25 years of his life, he lived with recurrent bouts of prostate cancer.

But unlike two other iconic 20th century campaigners against structural injustice, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., he lived to see the first fruits of his radical but peaceful promotion of fundamental change in his own society. Not only that, he lived to bring the political leaders who liberated South Africa under the same piercing – at times angry – scrutiny to which he subjected the apartheid and other oppressive governments.

Tutu’s advocacy ranged widely, beginning with appeals for sanctions against apartheid and continuing with campaigns against homophobia, for gender equality, against child marriage, against the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, against oppression in nations from China and Burma to Panama, and in support of the “second wave” of liberation which saw the growth of multi-party democracy across Africa from 1989.

The common factor which underlay Tutu’s activism was his deep-rooted faith and its implications for how people – and later the environment – should be treated. If there was one thing which enraged him, it was to see the powerful inflict suffering on “so-called ordinary people”— “so-called because in my theology nobody is ordinary.”

He believed that every human being is created in the image of God, to be held in awe and reverence as if he or she is God. Therefore to mistreat a human being is not simply unjust, nor simply painful for the victim: it is blasphemous because it is “spitting in the face of God”.

“When I see innocent people suffering,” he wrote, “pushed around by the rich and powerful, then, as the prophet Jeremiah says, if I try to keep quiet it is as if the word of God burned like a fire in my breast.” As he rose rapidly through the ranks of church leadership in the 1970s, he recognised that he was placing his life at risk. But he felt compelled to speak out, no matter the consequences.

Part of a new generation of church leaders.

In the 1970s, he was one of a generation of black church leaders who took office in multiracial South African churches, 80 percent of whose members were black, but which had until then been led by mostly white clergy. Emboldened by a confidence engendered by the philosophy of black consciousness, combined with theological studies undertaken abroad in Western democracies, the black theologians transformed churches into harbingers of what a liberated South Africa could look like.

With South Africa’s most militant black leaders in prison, exile or internal banishment, and with the growing militant labour unions operating mainly on shop floors, the church leaders used their pulpits to become the most prominent anti-apartheid voices within South Africa at the time.

There was no difference between Desmond Tutu and most other black church leaders of his generation in their commitment to liberation. What most distinguished Tutu was his extraordinary powers of rhetoric and his willingness to alienate white Christians in declaring what he believed to be the truth.

The issue prompting his then-controversial appeals for economic sanctions against South Africa by the international community was the policy of forced removals. The apartheid government removed an estimated 3.5 million people – more than 10 percent of South Africans – from homes where many had lived for generations and dumped them to eke out an existence in poverty-stricken rural “homelands”.

In sharply-worded, no-holds-barred attacks, Tutu skewered those he held responsible for apartheid’s suffering, using language which got under the skins of white racists in a way few others could. When Cabinet ministers responded with fury, he would raise the stakes with even more defiant attacks. He told the apartheid government that they would go the way of Nero in Rome, of Hitler in Germany, of Amin in Uganda and Somoza in Nicaragua: they would, he said, “bite the dust, and bite it comprehensively.”

Appalled by human suffering, he angrily confronted apartheid leaders – and post-democracy leaders as well.

When P. W. Botha, the apartheid president who operated military and police death squads, wagged his finger at him during a confrontation in 1988, Tutu angrily shook his finger back and told him: “Don’t think you’re talking to a small boy!” Abandoning restraint, he tore into Botha. “I don’t know whether that is how Jesus would have handled it,” he said ruefully later, but “our people have suffered for so long [and] I might never get this chance again.”

As a consequence, Tutu was vilified and demonised, seen by some of his co-religionists as literally the devil incarnate for his strident denunciations of apartheid and support for sanctions to destroy it. He used to say that he had developed the hide of a rhinoceros in the face of attacks by white South Africans, but he actually found it painful to be the object of such hate. When, in contrast, he was lionised abroad, he became susceptible to the adulation which celebrity brought. But his spiritual confessor used to say that he had an acute self-awareness, and Tutu’s coded acknowledgement of how he loved the limelight could be heard in his phrase, “I love to be loved”.

Once political apartheid was overthrown, and Tutu’s friends had come to power, some of them began to disclose to him in confidence the mistakes their movement was making. He became an early critic of the new government, unable to keep to himself the criticisms which once again “burned in his heart”. Again, he denounced what he saw as misrule, sometimes using language as extravagant as that he had used against the perpetrators of apartheid – even against Mandela.

When “ordinary” people suffered, the old anger would return. In 2006, when Jacob Zuma went on trial for rape, his supporters heaped vilification and abuse on Zuma’s accuser. Tutu pronounced Zuma unfit to rule because he failed to repudiate their behaviour. A month before Zuma became president in 2009, Tutu noted that he was doing so under suspicion of corruption, fraud, racketeering and money laundering: “Is this why people died fighting apartheid?” Tutu asked. “Is this why people went into exile? Is this why people were tortured?”

Tami Hultman / AllAfrica .Archbishop Desmond Tutu interviewed in Cape Town in 2007.

Again, those he censured often responded with scorn and derision. Typically, he would respond simply by saying he was “sad” when he saw allies in the struggle failing to live up to the high standards he set for them.

Biographical sketch

DESMOND MPILO TUTU was born on October 7, 1931, the third child of Aletta Dorothea “Matse” Matlhare, a domestic worker, and Zachariah ZeliloTutu, the principal of a church-run primary school. His older and younger brothers both died in infancy, leaving him with an older sister, Sylvia, and a younger sister, Gloria. The mortality rate in the family – 40 percent – was average for a black South African family at the time.

Desmond contracted polio before there was a vaccine and at a time when the death rate of sufferers in South Africa reached 25 percent. His father prepared for a funeral. Although he recovered, his right hand atrophied, leaving him with a weak grip and a lifelong habit of rubbing it to improve his circulation. Later, the propagandists of the apartheid-era South African Broadcasting Corporation turned the habit against him when he was under attack, their cameras zooming in on his hands as if he was wringing them in guilt.

He remained “very delicate” through childhood, remembered his older sister, Sylvia, who died in 2020. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis at 15, when it was a disease of epidemic proportions in the overcrowded townships of post-World War II Johannesburg. At one stage during treatment, while coughing up blood, he resigned himself to death. He likely owed his life to the monks of the UK-based Community of the Resurrection (CR)—among whom the anti-apartheid activist Trevor Huddleston was the best known—who found him one of the few hospital beds available for black South Africans with TB.

Admiring the medical staff at the sanatorium to which he was confined for 21 months, he aspired to study medicine at the University of the Witwatersand. He was admitted to the medical school but his family did not have the resources to pay for his study, and he followed his father into teaching instead.

The radical Mrs Tutu

In 1955, he married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, also a teacher and a friend of his younger sister, Gloria. Leah – of whom he used to say that she was much more radical than he – was to become central to his achievements over their 66-year marriage. Soon after they married, Leah willingly joined him in giving up her teaching salary when they both decided to give up the profession in protest against what he called the “thin gruel” of apartheid education.

Although active as a lay Christian, Desmond had not previously aspired to enter the church. “It wasn’t for very highfalutin’ ideals that that I became a priest,” he said later. “The easiest option was going to theological college.” Leaving their two toddlers – Trevor Tamsanqa and Theresa Thandeka – with his parents, Desmond went to college in Johannesburg and Leah to a remote rural hospital to train as a nurse. Reunited afterwards, she struggled against the church’s disregard of priests’ wives. When Desmond was sent to Britain to study at King’s College, London, in 1962, she successfully forced a showdown with the celibate monks who expected her to leave behind her children yet again.

After four years and with Honours and Master’s degrees in theology, Desmond returned home with Leah and their four children, Trevor and Thandi having been joined by Nontombi Naomi, born in Johannesburg, and Mpho Andrea, born in London. He taught at his alma mater, St. Peter’s College in Alice in the Eastern Cape, which had been forcibly removed from Johannesburg under apartheid and had become part of the inter-church Federal Theological Seminary (Fedsem) next door to the University of Fort Hare.

Tutu was to say later that he returned to South Africa as a theologian who did not question conventional Western thinking. But his first-hand exposure at Fedsem to the thinking of students such as Steve Bikoand Barney Pityana, and his first experience of the use of state power to suppress dissent at Fort Hare in 1968, began to change his worldview.

Speaking three decades later, Professor Pityanadescribed what happened when the university authorities expelled the whole student body after protests: “We had been surrounded by police, with dogs snarling at us. We were petrified, for nearly two hours. Some people were crying… The staff of the university, the white people—some of them armed—these professors were watching and nobody said a word, nobody.… Desmond [came] almost from nowhere, in a cassock… broke the police cordon and came to be among us. I recall moving scenes of young women kneeling to pray with Desmond for blessings. Even today when I recall that I get very emotional.”

After subsequently teaching at the then University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland in Roma, Lesotho, Tutu was offered the job of Africa secretary to a theological education fund of the World Council of Churches. Based in London, he paid 48 visits to 25 African countries over a three-year period, learning of successes achieved and pitfalls encountered by newly-independent nations across the continent. This was to stand him in good stead 30 years later when he began, earlier than most, to see the mistakes being made in newly-liberated South Africa. He also honed his theological thinking, drawing equally on what he saw as the strengths of the black theology being developed in the United States, African theology in newly-independent African nations and the liberation theology of Latin America.

When Tutu returned to South Africa as the first black Anglican dean of Johannesburg in 1975, he brought to the post a nuanced view of leadership in a South Africa which was about to be thrown into tumult by the Soweto uprising. “I am firmly non-racial and so welcome the participation of all, both black and white, in the struggle,” he said. “But… at this stage the leadership of the struggle must be firmly in black hands…. However much [whites] want to identify with blacks it is an existential fact… that they have not really been victims of this baneful oppression and exploitation. It is a divide that can’t be crossed and that must give blacks a primacy in determining the course and goal of the struggle. Whites must be willing to follow.”

Soon after Nelson Mandela was released from prison in February 1990, he visited a meeting of Desmond Tutu’s Synod of Bishops Soweto to thank the churches for their role in opposing apartheid.

Promoting sanctions

From the pulpit of St Mary’s Cathedral, Johannesburg, he began to speak out against apartheid, becoming widely known first for a 2,600-word letter to apartheid Prime Minister B.J. Vorster, in which he wrote of “a growing nightmarish fear” of the inevitability of “bloodshed and violence” unless a national convention of legitimate leaders was convened to steer the country to democracy. Five weeks later the children of Soweto initiated the uprising of June 16, 1976.

He was not to stay at the cathedral for long. Within a year he was elected bishop of Lesotho and then recalled home two years later to become general secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC). It was in that capacity that he first saw the extent of the suffering caused by forced removals, and was moved particularly by an exchange with a young girl in one of apartheid’s rural dumping grounds. It ended with him asking her: “What happens if you can’t borrow food?” She replied: “We drink water to fill our stomachs.”

In the first of a series of letters to P.W. Botha, he angrily denounced the removals as “utterly diabolical and unacceptable to the Christian conscience…” Ignoring church lawyers’ warnings that he risked being jailed under the government’s draconian “Terrorism Act” of 1967, he began lobbying for sanctions overseas and was instrumental in persuading the Canadian and French prime ministers, and the United States Congress, to impose sanctions in the 1980s.

The drive for sanctions, perceived by the apartheid government as a bigger threat to its existence than the liberation movements’ armed struggle, and the hatred it engendered among white South Africans, likely generated the most serious threats to his life. An order by a South African army officer to security forces to shoot him and his fellow clergyman, SACC President Peter Storey was disobeyed by black soldiers; the sabotage of the front tyre of a hired car at an airport was thwarted by an observant television cameraman and, ironically, a young white military officer; and an unsuccessful attempt by the “Civil Co-operation Bureau”, which operated military death squads, to recruit an ex-convict to kill him.

If the government had been brazen and determined enough, they could have had him killed. They made more serious attempts on the lives of other church leaders, notably Smangaliso Mkhatshwa, secretary-general of the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference, and Frank Chikane, a successor to Tutu as general secretary of the SACC. What probably saved Tutu was the fact that assassinating him—even jailing him—would have precipitated the very sanctions the government sought to avoid, especially after the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded him their 1984 Peace Prize.

Not a pacifist

Desmond Tutu’s advocacy of sanctions was strongly resisted not only by supporters of apartheid, but by its liberal opponents. He argued with the opposition parliamentarian, Helen Suzman, telling her that when she said sanctions wouldn’t work she was saying in effect that the last peaceful option for ending apartheid had been exhausted.

For Tutu, accepting that conclusion would have been momentous, for he would have had no option but to subscribe to armed struggle. Never a pacifist in the mould of Gandhi or King, he embraced instead the just war theory. Originally developed by the African saint, Augustine of Hippo, and later the Italian monk, Thomas Aquinas, just war holds that it is legitimate to turn to violence when all peaceful means of bringing about change have been exhausted. When abroad, Tutu vigorously defended the liberation movements’ decisions to launch armed struggle, but he never reached the point of endorsing them himself.

Preaching peace on the streets

There was a period during the 1980s when international church campaigners for justice saw Tutu, at least in the West, as the world’s most prominent religious leader after Pope John Paul II. The difference between the two leaders, one observed, was that John Paul II preached freedom and peace from the pulpit, Tutu – with fellow church leaders – promoted it on the streets.

During the final uprising against apartheid which began in 1984 and continued until the elections of 1994, Tutu, Chikane, Storey, Tutu’s deputy in the church, Michael Nuttall, and countless other clergy were repeatedly called upon to defuse violent confrontations between police and angry young people.

Time and again, Tutu moved into the space between young people armed with bricks and stones on one side, and troops and police and soldiers with fingers on their triggers on the other. Time and again he roused the passions of the young with rabble-rousing rhetoric which scared the bejesus out of some of his white bishops, then channelled the anger of the crowd into constructive action with humour and stern admonition.

And when black South Africans, penned into ghettoes by troops and police, turned on one another at the height of the internal struggle against apartheid, Tutu joined his fellow clergy in facing down youngsters determined to attack those they saw as collaborators with apartheid.

Most memorably, supported by friends such as Simeon Nkoane, a monk who became a bishop on the East Rand, and Leo Rakale, the monk who was the model for one of Alan Paton’s principal characters in Cry the Beloved Country, he stepped in to rescue “impimpis”—those accused of being police spies—from fiery, agonising deaths at the hands of comrades who sought to force tyres soaked with petrol over their bodies, then to set them alight.

The response of a British father who joined an adoring congregation in St. Alban’s Cathedral, north of London, to celebrate Tutu a few years later, was typical: “That,” he told his son, “is a very brave man.” In New York, it was more his post-Nobel prize celebrity which evoked similar reactions. As he processed out of a packed Cathedral of St. John the Divine, young people pressed to get close enough to touch his cassock as he passed.

Desmond Tutu visiting victims of intra-communal violence which broke out in black communities in the early 1990s. The violence was sparked or stoked by forces of reaction seeking to stall the transition to democracy.

Efforts to avoid political partisanship

Desmond Tutu never joined the African National (ANC), which has been the governing party since apartheid fell. But he was publicly associated with the movement from the time he became an early supporter of the domestic campaign to free Nelson Mandela. When abroad, Tutu would insist on meeting the ANC’s exiled leader, Oliver Tambo – viewed by the apartheid government as a terrorist. Upon his return, he would announce his meetings and expound on Tambo’s virtues as a committed Christian.

However, as a church leader Tutu made efforts to eschew partisanship, agreeing in the 1980s to become a patron both of the United Democratic Front, aligned with the ANC, and the National Forum, a rival, black consciousness-aligned group of organisations. Most controversially in the church, soon after Mandela was released Tutu banned priests in his church from joining any political party on the grounds that it would prevent them from ministering in congregations whose members belonged to competing parties.

Although it did not become apparent to most white South Africans until after Mandela’s release, Tutu had deep compassion for them. Apartheid dehumanised the oppressor more than it dehumanised the oppressed, he said. He supported conscientious objectors who refused compulsory military service and helped some flee abroad. He was thrilled when hundreds of young white South Africans joined the 1989 Defiance Campaign in Cape Town, which ramped up pressure on the newly-elected president, F. W. de Klerk, and helped to clear the way for Mandela’s release.

He had a particular respect for repentant Afrikaners, and he longed in vain for De Klerk to follow in the footsteps of the dissenting white church leader, BeyersNaude, who broke with his community and uninhibitedly backed the ANC in its struggle.

Mediation and reconciliation

After Mandela’s release, Tutu announced that he had been an “interim leader” while political leaders were jailed or in exile. He would still speak out on political issues as a church leader, he said, but he would now take a lower profile. When intra-communal violence broke out in black communities – sparked or stoked by forces of reaction seeking to stall the transition to democracy – Tutu and his fellow church leaders moved instinctively from anti-apartheid campaigning to trying to mediate among the leaders of rival political parties and defusing violence among their supporters.

It was presumably both for Tutu’s credibility as an outspoken supporter of liberation and his role as a mediator that in 1995 Dullah Omar, President Mandela’s justice minister and an admirer of Tutu’s peacemaking on the streets, recommended him to chair of the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

A uniquely South African truth-telling

The commission was the product of a toughly-negotiated compromise between, on the one hand, those in the liberation movements who wanted apartheid leaders put on trial, and on the other, the leaders of the old regime who wanted blanket amnesty for their security forces, as had been granted in other countries transitioning to democracy. The uniquely South African compromise – amnesty but only in exchange for the truth – was forced upon Parliament by the fact that the liberation movements did not have military power commensurate with their legitimacy, and the old regime did not have enough legitimacy to continue to rule with military power alone.

Although the commission was thus born as a consequence of realpolitik, Tutu seized it as an instrument of reconciliation. His approach was in line with a three-step process founded in his faith. In the first step, he said, those who had wronged others needed to confess their crimes – as they were required to do to receive amnesty. In the second step, he urged survivors and victims to consider forgiving perpetrators.

In the pulpit, Tutu would preach that victims were under a “Gospel imperative” to forgive. But then, in the third step, those who had committed wrongs had to make restitution: “If I have stolen your pen, I can’t really be contrite when I say, ‘Please forgive me,’ if at the same time I still keep your pen. If I am truly repentant, I will demonstrate this genuine repentance by returning your pen.”

The most trenchant criticism of the truth and reconciliation process is that it failed to deal with mass violations of human rights such as forced removals, the pass laws which restricted the movements of black South Africans and an inferior education system. The consequence was that the beneficiaries of apartheid were able to transfer the principal blame for the suffering it caused on a small coterie of its enforcers.

However, dealing with those mass violations was not the mandate given to the commission by Parliament. Its task, initially to be completed in 18 months, was limited to investigating and reporting on gross violations of human rights—defined as killing, abduction, torture, and severe ill-treatment—in the period between the Sharpeville massacre of 1960 and Mandela’s inauguration in 1994.

Within those constraints the commission succeeded in identifying and formally declaring as victims or survivors of violations more than 21,000 people. Backed by the threats of prosecutors, it also succeeded in flushing out members of police death squads, although the apartheid military largely boycotted the commission. While this has not yet been adequately researched, the process also reconciled many in black communities who fought on different sides of the struggle.

Tutu’s two greatest disappointments were the failure of most white South Africans to take the hand of reconciliation offered to them by black South Africans, and of the ANC government’s failure to prosecute those who refused to apply for, or were denied, amnesty. He was also upset that the government failed to implement in full the commission’s recommendations for token monetary grants which were part of its proposals for restitution.

President Clinton and Vice President Al Gore meeting with Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the Oval Office on May 19, 1993.Clinton used the meeting to announce his administration’s recognition of the Angolan government. Tutu and Gore knew one another from their previous service as members of Harvard University’s Board of Overseers.

Once the commission had completed its work, he was judged by most of his fellow commissioners to have been essential to the process, although he came in for widespread criticism for being overly sympathetic to Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and treating her with kid gloves during a hearing into human rights violations committed by her bodyguards during the late 1980s.

International campaigns

In 1988 Desmond Tutu was elected president of the All Africa Conference of Churches. Armed with his 1970s experiences, he made it a priority to travel to countries governed by oppressive rulers. Trading on his anti-apartheid credentials and celebrity to gain access to heads of state, he secured local church leaders audiences to press their cases for greater freedom for their people.

He also campaigned publicly for democracy and human rights. In Mobutu’s Zaïre, Mengistu’s Ethiopia, Bashir’s Sudan and General Manuel Noriega’s Panama, he preached to crowds, condemning specific human rights violations experienced in South Africa. His audiences responded with delight as they realised he was listing violations also being perpetrated upon them, although in Addis Ababa he was told an interpreter had been too scared to translate him accurately into Amharic.

Later, President Mandela sent him to Nigeria to plead for the release of M.K.O. Abiola, the winner of the 1993 election who had been detained after the military annulled the result. In an audience with General SaniAbacha, Tutu insisted on seeing Abiola, then publicly lambasted the general for lying to him about the conditions of Abiola’s detention.

After the 1994 Rwandan genocide and the subsequent flood of refugees into what was then Zaïre, he co-chaired a summit of heads of state from the Great Lakes Region, organised by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter. There he challenged Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni over whether the death penalty should be used in trials of the perpetrators of the massacres.

It was one of Tutu’s aphorisms that an “African communist” is a contradiction in terms, if communism is defined as atheistic and materialistic – Africans are naturally spiritual beings, he said. On visits to Angola and Ethiopia, he asked ruling party officials how many true Marxists there were in their ranks – then relayed their surprisingly small estimates to delighted local church leaders.

Spirituality

While Desmond Tutu was an enthusiastic ecumenist and promoter of inter-faith dialogue, he remained first and foremost an Anglican Christian, whose life was sustained by a deep spirituality and a firm faith – never lost in the face of injustice, despite sometimes clinging to it “by the skin of my teeth”.

He dismissed the Western convention of distinguishing between religion and politics. Separating the sacred from the secular was, he said, a result of the “baneful influence” of “Hellenistic dualism” on Western thought. He instead advocated an African worldview: God is the God of all life, whether religious or political. In this he could impress even scepticalAmerican neoconservatives: the Catholic intellectual, Michael Novak, reviewing a collection of his writings and sermons, concluded: “The consistency of the thing is beautiful.”

Tutu was an articulate exponent of what is described in his father’s home language – isiXhosa – as ubuntu and in his mother’s – Setswana – as botho, expressed best in the proverb “a person is a person through other people”. In his formulation, ubuntu or botho is Africa’s gift to the world: a model for expressing the nature of human community and of all creation as a delicate network of interdependence, one which speaks of a global society in which there are no outsiders but all are insiders, created in God’s image, and in which the welfare of every individual depends on the welfare of the other.

Although he supported the secular foundation of the South African state, he opposed too rigid a separation of church and state. He thought it too sharply drawn in the United States and was disappointed when the new, democratic South African Parliament adopted a practice of opening proceedings with a time of silence. He felt that since the vast majority of South Africans were believers, there should be a rotating roster of prayers reflecting different religious traditions.

No façade

Desmond Tutu had extraordinary personal qualities. The South African writer and Nobel literature laureate Nadine Gordimer said of him: “He has no façade. The open interest, the fellow warmth that radiate from him… are what he is. I’d call his lack of self-consciousness one of inherent gifts, the others have been developed by the exercise of character, the spiritual and intellectual muscle-building he has subjected and continues to subject himself to in service of the human congregation.”

Humour, deployed to serious effect when trying to defuse violence, and cackles of uproarious laughter were a Tutu trademark. But he observed that laughing and crying were often separated by a thin line, and he cried nearly as easily as he laughed – again, particularly when he witnessed the suffering of the innocent.

His lively personality was also the flip side of up to six or seven hours of silent prayer or worship spread through the day, usually beginning at around 4 am when he was archbishop. A Canadian journalist who travelled with him on a difficult mission to Liberia wrote: “Inside this man whom much of the world knows as an ebullient, laughter-filled extrovert, a Nobel peace laureate who holds audiences and congregations spellbound, lives a meditative, contemplative person…”

Tutu could combine the strict demeanour of an authoritarian bishop with the compassion of a gentle pastor who had an extraordinary capacity to fix in his mind and remember intimate personal details about people he had just met. His rapid ascent from priest to college lecturer to dean to bishop meant that his assignments as a full-time parish priest were short. But he took pride in his pastoral skills and combined his general secretary’s duties at the South African Council of Churches with part-time supervision of a parish in Soweto.

Bishop Desmond Tutu arguing the need for bringing pressure to bear on the apartheid government in an Oval Office meeting with President Ronald Reagan on December 7, 1984 – the first meeting between an anti-apartheid leader and the U.S. president. Reagan remained implacably opposed to sanctions. The U.S. Congress approved them, then overrode a veto by Reagan in one of the biggest foreign policy defeats of his presidency.

Tutu’s causes

He fervently supported the ordination of women as priests, the ordination of gay and lesbian priests and the blessing of same-sex unions, on the same grounds that he opposed apartheid – he could not accept discrimination against a group of people on the basis of an attribute they could not change, whether it was their race, their gender or their sexual orientation. In this he dissented from the stance of African Anglican churches, having to watch from the sidelines in retirement as his youngest daughter, Mpho, gave up her licence to act as a priest in South Africa when she married her wife.

He threw himself unreservedly and passionately into the causes he supported, often experimenting with new initiatives based on his gut feelings and uninterested in conducting post-mortems when they failed. He freely took risks, such as when, at the suggestion of an evangelical Oxford University chaplain, he made an “altar call” to a largely secular audience in the Oxford Union. Not a single person stood up to “give my life to Christ.” Apparently unfazed, he moved on with no sign of concern.

He could also be quietly and teasingly provocative, once strolling around during a meeting of Anglican archbishops in Northern Ireland wearing a newly-acquired fisherman’s sweater in rich Republican green.

Self-righteous and abrasive?

He recognised that during the early years of his public life, he owed much of his influence to journalists who reported what he was saying. As a result he gave priority to speaking to them and was on friendly terms with the vast majority. Tough questioning by critical reporters helped him hone his arguments, and he developed a particular regard for the most sceptical, enjoying sparring with them. He almost never spoke off the record and was known at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for his frankness.

He would not tolerate his integrity being impugned – he twice nearly derailed the commission in clashes with other commissioners when he felt it was being questioned. Damaging stand-offs were averted only when he brow-beat them into backing down.

But in public life, after years of denouncing injustice in no-holds-barred, unnuanced terms, once South Africa began to move to democracy, he began to feel that he had been too self-righteous and abrasive. He took to heart criticism from Lucas Mangope, one of the black leaders who took “independence” under the apartheid system, that the churches had isolated and failed to extend pastoral care to them.

Tutu had a rocky relationship with Prince MangosuthuButhelezi, who worked within the system but resisted pressure from the apartheid government for the Zulu nation to give up their South African citizenship. But neither man gave up on trying to reach out to the other. Buthelezi, an Anglican, regularly agreed to meet “my archbishop” when Tutu was trying to mediate peace in the transition to democracy, and Tutu subsequently invited him to family celebrations.

Raising money – and spending it

Tutu’s attitude to money was utilitarian and he was accused by many of being a spendthrift. His wife, Leah, sometimes teasingly described him as a professional beggar; when he became archbishop of Cape Town, he told his staff that he knew how to raise money, he certainly knew how to spend it but that he left church treasurers to manage it. After retirement he earned substantial sums on the American speakers’ circuit, where he was popular and highly regarded for his rhetorical skills. This secured him a financial independence which helped enable him to continue to speak his mind.

Except for travelling first class on airlines – enabling him to sleep properly and reducing the potential for other passengers to disturb him – he tried to live simply, retaining his home in Soweto until recently, and spending most of his time after retirement in a modest seaside suburb in Cape Town. His other tastes were also simple, and sweet: a rum and coke until medical treatment ended it, and rum raisin ice-cream if it was available. If it wasn’t, Leah would tell hosts, in choosing an alternative “just think of a five-year-old”.

His decision in 1975 to uproot his family from London and return home to become dean of Johannesburg, strained their marriage. Back at home, Leah was whipped by police in a way he never was and harassed by traffic policemen who once arrested her, handcuffed her and dragged her to a police charge office – for late payment of her car licence. He reserved a special anger for those he thought were punishing him by attacking his family, and he felt guilt for not being able to protect them.

A turning point in their marriage came for him when he was under fire from a police minister who was attacking him for his outspokenness. Should he keep quiet? he asked Leah. No, she said, she would far prefer him happy and imprisoned on Robben Island than unhappy and frustrated outside. She went on to march against apartheid with him.

He loved to give money away to his and Leah’s favourite causes, such as the nutrition clinics founded by his physician for more than three decades, Dr. Ingrid le Roux, and the work done by the renowned Stellenbosch University expert on tuberculosis, Professor Nulda Beyers. He and Leah were also patrons of the Phelophepa ( good clean health) Trains, bringing attention and support to trains operating as mobile healthcare hospitals in impoverished rural areas.

His vocation as a priest recognised no distinction between work and personal life, which meant that his family had to share much of their time with him with others. Challenged by an outside consultant when he first became archbishop to rank the priority of time with family against the priorities of his office, he refused.

He is survived by Leah, his children – Trevor Tamsanqa Tutu, Theresa Thandeka Tutu-Gxashe, the Reverend Naomi Nontombi Tutu and the Reverend Mpho Andrea Tutu van Furth, and by grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

John Allen, a former managing editor of AllAfrica, covered Desmond Tutu as a journalist for 45 years and was his press secretary for 13 of them. He is the author of the definitive Tutu biography, “Rabble-Rouser for Peace”, and the compiler and editor of three volumes of key Tutu texts. He has worked with the Apartheid Museum on “Truth to Power”, an exhibition on Desmond Tutu and the churches’ role in the struggle, scheduled to open in 2022.

allAfrica.com

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation