By Huang Meibo and Niu Dongfang

A train runs on the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway. Photo: Xinhua

It’s wrong to claim Chinese overseas investments are ‘debt trap’

In March 2021, Georgetown Law, the Peterson Institute for International Economics, AidData, Center for Global Development and Kiel Institute for the World Economy of Germany jointly issued a report titled “How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments”. Through a comparison of 100 sovereign debt contracts signed by Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank), China Development Bank (CDB), Chinese state-owned commercial banks and Chinese government departments and 142 sovereign debt contracts signed between Cameroon and bilateral, multilateral and commercial creditors, the report points to the differences in the lending rules between China and mainstream Western institutions such as the Paris Club in the four aspects:

First, Chinese contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses, which were introduced around the time of the inception of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). According to the report, confidentiality clauses would give rise to the problem of “secret debts” to countries across the Global South, and make it difficult for the West to calculate those countries’ debt sustainability.

Second, contracts offered by Chinese official creditors expressly commit borrowers to exclude the debt from restructuring in the Paris Club or any other multilateral restructuring, which hinders the implementation of the core principles of the Paris Club.

Third, Chinese contracts contain cross-default and cross-cancellation clauses, which tend to give China relational power over countries of the South and stronger influence over their domestic and foreign policies.

Fourth, Chinese loans to foreign countries require the maintenance of special accounts for the purpose of risk management, taking up the foreign exchange reserves of countries of the South and affecting the precision of Western analysis of those countries’ debt servicing ability.

Actually, the argumentation method and process of the report lack scientific basis, and its conclusions are untenable.

Problematic contract samples

The samples used in the report are seriously flawed. For example, the source of the contract samples is unclear, and the choices of samples and comparison methodology are subjective and biased. Therefore, the conclusions are hardly convincing.

The samples represent base evidence for the research and conclusion of the report, and the legality, authenticity and relevance of the source of evidence directly determine the neutrality, credibility and scientificity of the conclusions. While claiming all the contracts were obtained from open sources, the report accuses China of keeping sovereign loan contracts confidential and not transparent. The report does not explain a contradiction: How the researchers obtained their information if the contracts were confidential.

The report examined 100 sovereign debt contracts signed between 24 developing nations and China from 2000 to 2020, and compared them with 142 sovereign debt contracts signed by Cameroon between 1999 and 2017. The problem with this approach is the mismatch and lack of heterogeneity of the country chosen for comparison: Cameroon is only one country, and its financing needs and development structure are not sufficiently diverse and heterogeneous. Comparing a benchmark country with little variety and a group of 24 countries with great variety reduces the validity of the research conclusion.

Another problem of the report involves comparing 100 bilateral sovereign debt contracts of China with 142 multilateral and bilateral debt contracts of Cameroon. Of all the Chinese contracts, the 76 contracts signed by China Eximbank include preferential government loans, preferential buyer’s credit and buyer’s credit; the eight CDB contracts are in the category of development financial loans, which are basically commercial bank loans. In comparison, Cameroon’s contracts are mainly signed with multilateral development banks, with more favorable terms than the ones offered by China Eximbank.

Within the international development financing market, multilateral development banks, bilateral government aid agencies, development financial institutions and commercial banks are fundamentally different in their function, which is why government preferential loans, development loans and commercial loans constitute different types of loans, with different earning levels and means of risk prevention and control. The method used in the report, which is like comparing apples and oranges, makes the intent questionable.

A scientific and neutral research report would choose to compare the preferential loan contracts of China EximBank with similar contracts of government-backed institutions of preferential loans such as Agence française de développement (AFD), Japan International Cooperation Agency and KfW of Germany.

The failure of the report to provide equal numbers of similar bilateral sovereign loan contracts offered by Western countries reveals two things: First, the research method of the report is flawed, and the correlation between evidence and conclusion is insufficient. Second, the report seeks to make China the target for all while avoiding an assessment and judgement of bilateral lending institutions in the West.

On confidentiality clauses

According to the report, Chinese contracts contain “unusual” confidentiality clauses, which prohibit borrowers from disclosing clauses or the existence of debts. However, the principle of confidentiality is widely applied in international loan contracts, and the practice of not disclosing detailed information about the terms of loans is also quite common.

With few exceptions, creditors and sovereign debtors normally do not publish their contract texts in full. There is no uniform public disclosure standard or practice for bilateral official lenders. Even the authors of the report themselves admit “almost all OECD official creditors and non-OECD creditors have not publicly released their loan contracts.” Similar confidentiality clauses can be found in the official bilateral debt contracts of the AFD. The Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA), the Islamic Development Bank, the OPEC Fund for International Development and the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development all require the borrower to keep the documents and letters of the lender confidential. Even the Asian Development Bank has confidentiality clauses in its loan agreements. Debtor governments usually would not publish the text of their loan contracts either.

The above-mentioned examples show that setting confidentiality clauses is a common practice for lenders, yet the report singles out China, which is either due to a lack of understanding of common commercial practices or out of ulterior motives. Besides, China is not an OECD member, nor a party to the OECD creditor reporting system, the OECD Export Credit Group (ECG) or the Paris Club. Thus, it has no obligation to disclose its loan information.

On ‘No Paris Club’ clauses

According to the report, close to three-quarters of the debt contracts in the Chinese samples contain the so-called “No Paris Club” clauses, which expressly commit the borrower to exclude the debt from restructuring in the Paris Club of official bilateral creditors and from any comparable debt treatment. The report maintains that such clauses are inconsistent with China’s position and attitude on signing the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments. Such a one-sided conclusion picks only opinions in their favor. Without proper framing of the argument, it takes the Western model of sovereign debt treatment as the best option for the international community, and attempts to obstruct the efforts of emerging creditor countries to build a new scheme for sovereign debt treatment.

By underscoring the issue of Paris Club clauses, the Western countries are actually attempting to bring China into their framework of debt rules, while taking a step back lowering lending limits, and, at the same time, “softly absorb” the potential influence of China’s foreign lending with their framework of rules, and share in the reputational benefits of China’s sovereign lending.

The principles of the Paris Club reflect merely the interests of Western creditor countries and are not recognized by other emerging creditor countries. Arrogantly asking others to observe the rules shows a lack of “basic courtesy”. Commercial and official bilateral creditors that are not party to the Paris Club have no obligation to abide by these principles.

Over recent years, the international development financing market has gone through big changes, and the size of lending of Paris Club countries has dropped. That said, the current global debt governance system is still dominated by the “Paris Club – IMF – World Bank” structure of the West. But, with its expanded scale of China’s sovereign loans and the lending practice with Chinese characteristics, a new order that is more friendly to developing countries is in the making.

By calling into question the “No Paris Club” clauses in Chinese contracts, the Western countries are interfering in the free choice and internal affairs of debtor countries, casting a hegemonic shadow on the cause of international development financing.

The signing of loan contracts containing “No Paris Club” clauses between debtor countries and China is entirely based on the principle of equality and mutual benefit. It is a choice made by the debtor countries for the best of their national interest. All countries should respect the right of other countries to make their own choice, instead of taking the rules of the Paris Club as universal norms that must be observed by all.

In regulating the sovereign debt market, the Western countries have not given full consideration to the development financing needs of developing countries. Even worse, they have set obstacles for developing countries to make their own choices, and sacrificed their development rights to protect the so-called “Paris Club standards”. This is putting the cart before the horse. To put it bluntly, politicians and scholars in some developed countries believe they should not lend to developing countries, and also deny these countries the chance to borrow elsewhere.

On special contract terms

According to the report, compared with their peers in the official credit market, Chinese lenders offer contracts containing more elaborate repayment safeguards as well as cross-default, cross-cancellation and stability clauses, which gives them an advantage over other creditors. This conclusion ignores the particular context of China’s outward lending. To achieve sustainable development, developing countries need to fill a huge infrastructure gap. Since the early 20th century, the Chinese government and state-owned banks have provided a large amount of infrastructure loans to low-and middle-income countries.

However, as infrastructure investment and financing often involve substantial capital and increased risk, meeting the financing needs of developing countries has been a thorny issue. To ensure the safety of their sovereign loans, Chinese creditors have included commonly-accepted clauses such as cross default and cross cancellation in the contracts.

CDB is in essence a commercial bank. Compared to China Eximbank, it has a stronger need to manage credit and liquidity risks through contract terms and make use of credit enhancement instruments when lending to high-risk borrowers. Nevertheless, the text used in China’s loan contracts is the one generally accepted by the market and the terms are consistent with the principles of fairness and balance of rights and obligations of parties concerned.

As the times change, China’s presence in the international sovereign lending has become more significant. The international community needs to foster an objective view of China’s overseas sovereign lending.

Taking the financing needs of receiving countries as the top priority, China does not hesitate to take risks that other lenders cannot or are unwilling to take. This requires Chinese financial institutions to improve risk control mechanisms.

Despite their dire need for financing in infrastructure and other fields, commercial loans to developing countries, especially infrastructure loans, have been limited for a long time. This has become a major challenge to the world economy. The main reason is that infrastructure investment and financing requires significant capital input and involve a longer payback period.

In the past two decades, China has provided a large amount of bilateral loans to developing countries through policy and commercial funds, giving them important financial support for growing the economy, creating jobs, improving infrastructure and promoting industrialization.

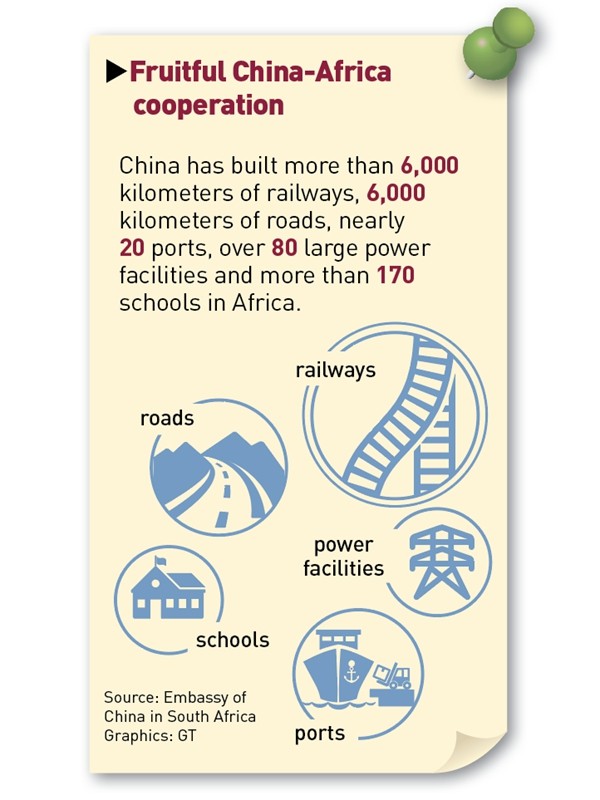

Source: Embassy of China in South Africa. Graphics: GT

And, policy loans provided through the bilateral channel is not a Chinese invention. Major Western countries all have similar official development financing institutions. The only difference is that these institutions have been on a decline. On the surface, such a decline is a manifestation of the budget constraints facing Western governments, but fundamentally, it is the result of liberal market ideology that makes livelihood projects a more likely beneficiary of ODA.

As a result, infrastructure projects urgently needed by developing countries receive little attention: ODA providers are not capable of funding such projects, and commercial institutions also take no interest in them due to high risks. China’s financing cooperation with other developing countries goes beyond the binary aid model of “government vs. market” of the West. It not only helps fill the funding gap, but also revolutionizes the concept of financing cooperation.

In terms of risk management and control methods, China explores replacing traditional means of ex-post dispute resolution with preventive measures taken before lending is provided. Such an approach encourages the debtor countries to become “responsible” borrowers in the process of development financing and increase their efforts toward sustainable development.

China’s financing model, combining policy-based funds with commercial funds, represents the future of development financing. In recent years, new types of mixed loans with official and commercial institutions as joint lenders have increased in the global financing market.

That said, when providing development financing to developing countries, it is important to control and reduce investment risks and ensure security of capital. Therefore, China tries to replace traditional means of dispute resolution with contract tools that prevent default in sovereign loans. Combining the practices of commercial banks and official institutions, Chinese contracts aim to secure maximum repayment by adjusting the standard contract tools, including setting up a revenue account based on the proceeds of the project to provide additional funding for debt repayment and relieve the pressure on government budget.

It is a legitimate measure to ensure the capital safety of lenders and a commonly-accepted commercial practice. It is also a practice adopted by some OECD official creditors – as pointed out in the report, 7 percent of OECD official creditors sampled use repayment security devices.

Arrangements such as default clauses, to some extent, constrain the debtors to fulfill their obligations, which is the very purpose of signing a contract. It urges debtor countries to properly manage their debt and fulfill repayment responsibilities, and become “responsible” borrowers with international credibility, while enjoying convenient access to loan concessions. This helps to enhance the countries’ reputation in the international development financing market and ultimately contributes to their economic and social sustainability.

The authors are from Shanghai University of International Business and Economics.

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation