By Jessica Durdu

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio holds a joint press conference with Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness (not in the photograph) in Kingston, Jamaica, March 26, 2025. /CFP

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s recent remarks in Kingston, Jamaica, reflect a deepening anxiety within Washington over China’s growing influence in the Caribbean and the broader developing world.

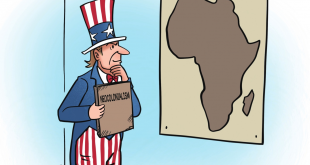

Rubio’s critique of China’s investment practices as “predatory” and detrimental to local economies is not a new narrative; it is a recurring theme in the U.S.’s broader strategy to counter China’s expanding global footprint. However, behind these criticisms lies a more complex and strategic reality: the shifting dynamics of the global political and economic order; the decline of the Washington Consensus, the economic policy recommendations for developing economies; and the emergence of China as a viable alternative investment partner.

For decades, the global financial architecture has been shaped by Western-led institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank. These institutions, often operating under the ideological framework of the Washington Consensus, have imposed stringent economic conditions on recipient countries, frequently prioritizing market liberalization, austerity, and political alignment with Western interests over sustainable development or local needs. The conditionality attached to IMF and World Bank loans has left many developing nations in cycles of economic vulnerability, political instability, and diminished sovereignty.

Rubio’s assertion – that China’s infrastructure financing puts countries in long-term financial distress – is based on the tradition of Western-led financial order that subjected developing nations to similar forms of economic dependence and political leverage for decades, and the thinking that China would also do the same.

China’s rise as a global lender and investor represents a fundamental challenge to this system. Through initiatives such as the Belt and Road, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the New Development Bank (NDB) launched with other BRICS partners, China has pioneered a model of economic engagement that is markedly different from the Western approach. Unlike the IMF and World Bank, which tie financial assistance to political and economic reforms that align with Western interests, China’s model emphasizes mutual benefit, infrastructure development, and long-term economic integration.

The AIIB and NDB, for example, are multinational platforms where developing nations have a greater voice in decision-making processes. This shift has empowered many countries in the Global South to diversify their economic partnerships and reduce their dependence on Western financial institutions.

Ethiopians participate in the opening ceremony of the “Seagull Talent Nurturing Project” in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Sept. 17, 2024. /CFP

Rubio’s concern about China’s investment practices, particularly the claim that Chinese companies secure contracts through unfair competition and subsequently impose financial strain on host countries, reflects a degree of strategic inconsistency. The U.S. itself has a long history of using economic leverage and political pressure to secure favorable terms in international trade and military contracts. A notable recent “unfair practice” example is the sale of F-35A fighter jets to Greece and the denial of the same to Türkiye, a fellow NATO member.

Rubio’s assertion that Chinese infrastructure projects fail to benefit local economies because Chinese companies often bring their own workers also warrants closer scrutiny. While Chinese firms deploy a number of skilled Chinese workers to execute large-scale infrastructure projects, the know-how is shared with local workers, and studies show that BRI projects have contributed to job creation and skills transfer in host countries.

In Ethiopia, for example, Chinese-funded infrastructure projects have created over 28,000 direct jobs for locals, with additional indirect employment in sectors such as logistics, maintenance, and retail. In Kenya, most of the workers who built the Standard Gauge Railway with technology and funding from China were Kenyans. In Pakistan, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor has generated over 236,000 jobs across sectors including energy, transport and construction, and more than half of them are held by Pakistanis.

The broader geopolitical undertone of Rubio’s remarks reveals Washington’s underlying objective: to contain China’s influence in the Caribbean and beyond. The Caribbean holds strategic significance for the U.S. due to its proximity and historical ties, but Washington’s engagement in the region has often been characterized by economic conditionality and political interference.

In contrast, China’s approach, focused on infrastructure, trade, and capacity building, offers Caribbean nations an alternative model of engagement. If the U.S. wishes to counter China’s influence in the Caribbean, it will need to present a more compelling and constructive alternative rather than relying on negative framing and strategic fearmongering of investments.

Developing nations are not passive recipients of Chinese investment; they are active participants in a recalibrating global order, seeking to maximize their strategic and economic interests. If Washington seeks to rebuild influence and credibility in the Caribbean and the broader developing world, it must move beyond Cold War-era rhetoric and engage with partner nations on more equal and mutually beneficial terms.

Jessica Durdu, a special commentator on current affairs for CGTN, is a foreign affairs specialist and PhD candidate in international relations at China Foreign Affairs University.

cgtn.com

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation

Africa -China Review Africa -China Cooperation and Transformation